My Modern Met - Jessica Stewart on August 21, 2019

There’s a lot of talk these days about GMOs and trying to eat more natural foods, but the concept of manipulating crops has been around since ancient times. Of course, the type of genetic modification practiced to transform wild organisms into domesticated crops is quite different than the genetic engineering of today. But still, you’d be surprised by how different many of the common fruits and vegetables we take for granted today are the product of selective genetics.

Early farmers weren’t modifying their crops to resist pesticides, but rather selectively growing them to highlight their most desirable attributes. That often meant bigger and juicier produce, some of which is impossible to find in the wild. So while today a ripe, plump peach is the norm, the reality is that they were once salty and small, with very little flesh. Tomatoes and cucumbers are two other common produce items that have seen exponential growth in size and variety over time.

Common fruits and veggies have undergone a makeover over the centuries. Check out some interesting examples of just how different undomesticated produce can look.

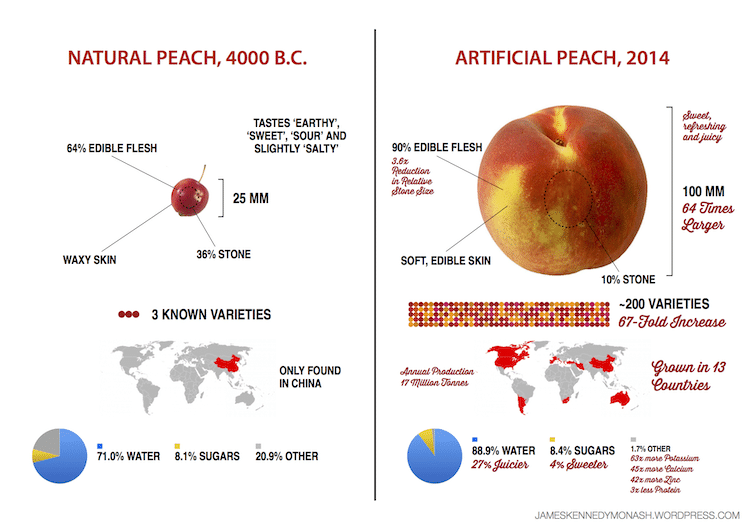

PEACH

Photo: Stock Photos from Kovaleva_Ka/Shutterstock

The modern peach has origins in China dating back to the neolithic period, with evidence pointing to their domestication around 6000 BCE. Australian chemistry teacher James Kennedy created an eye-opening infographic highlighting some of the differences between the original, natural peach and the one we find today. Not only were peaches much smaller, but their skin was waxy and the pit took up most of the space within the fruit. Over time, the best peaches were selected to create the soft, fleshy skin and succulent flesh we now associate with the refreshing fruit.

Photo: James Kennedy

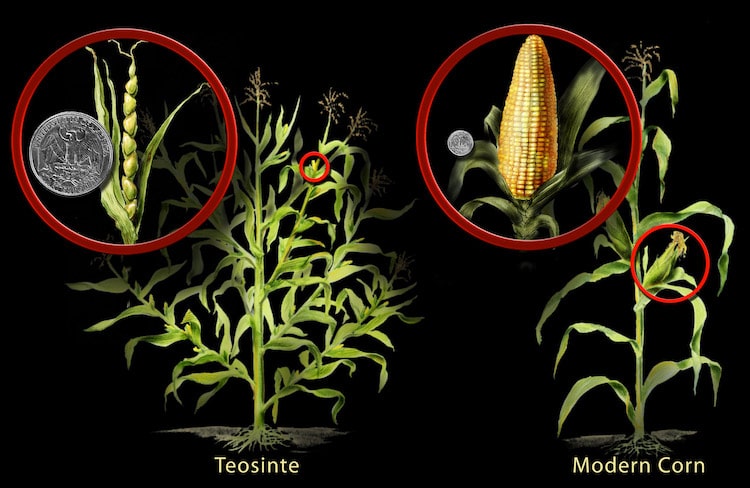

CORN

Photo: Stock Photos from Zeljko Radojko/Shutterstock

Yet another crop that’s undergone an amazing transformation is corn. First domesticated by the indigenous people of Mexico about 10,000 years ago, wild corn bears little resemblance to what we now see in the produce aisle. Corn’s origins have been linked to a grassy flowering plant called teosinte. Only one cob sprouted per teosinte plant, growing around one inch long. Unlike the hundreds of kernels found today on a cob, a teosinte has only 5 to 10 individually encased kernels on its cob. The taste was also much more starchy, like a potato. Over time, farmers worked the plant to become much longer, easier to peel, and with more plentiful and sweeter kernels. This infographic helps explain corn’s evolution into today’s popular food item.

Photo: Nicolle Rager Fuller, National Science Foundation

BANANA

Photo: Stock Photos from bitt24/Shutterstock

Packed with nutrients and covered with a peel-able flesh, the conveniently shaped banana may seem like the perfect fruit. But the reality is that the banana as we now know it is the product of hard work. Cultivation began sometime between 5000 BCE and 8000 BCE thanks to farmers in Southeast Asia and Papua New Guinea. One wild ancestor, the Musa acuminata, has slender fruit, which are berries, and contain between 15 to 62 seeds. Another Musa balbisiana has a more substantial looking fruit that is filled with hard, inedible seeds. It’s thought that these two plants were bred to produce a hearty fruit that, over time, contained just the edible pulp, eliminating the seeds.

Interior of unripened wild banana. (Photo: Warut Roonguthai [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

EGGPLANT

Photo: Stock Photos from PosiNote/Shutterstock

A wide variety of different cultivators are used to produce eggplant to local tastes. The purple eggplant, with its long and ovoid shape, is most common to Europe and North America. Across Asia and India, a huge variety of sizes and colors—including white, yellow, and green—are readily available. As part of the nightshade family, it’s believed to have its origins in the Solanum incanum. Also known as bitter apple or thorn apple, this plant still grows in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East.

Solanum incanum. (Photo: Nepenthes [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

WATERMELON

Photo: Stock Photos from 5 Second Studio/Shutterstock

Most are familiar with the 20th-century advent of the seedless watermelon, but this is just the latest development in a long line of changes to the fruit. 17th-century still life paintings demonstrate just how different ripe watermelons looked, with a segmented interior that contained much less flesh. It even appears much paler in comparison to what we see today. The classic watermelon red that’s synonymous with the fruit is due to the presence of lycopene. Natural watermelons were selectively bred to increase the amount of lycopene in the fruit’s placenta—the part we eat. Check out this infographic to see even more differences between the watermelons of yesterday and today.

“Pineapple, watermelons and other fruits” by Albert Eckhout, 17th century. (Brazilian fruits) (Photo: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

CARROT

Photo: Stock Photos from Olga Bondarenko/Shutterstock

If you’ve ever seen Queen Anne’s Lace growing wild on the side of the road, you may not have realized that this flowering plant is the forerunner of the domesticated carrot. Daucus carota is the scientific name of this plant, and while its root is edible when young, it soon becomes too woody to be consumed. Its leaves may also cause a skin inflammation known as phytophotodermatitis.

The modern carrot is a subspecies of Daucus carota that most likely originated in Persia. Over time it was selectively bred to reduce woodiness and bitterness. Interestingly, they were first used more for their leaves than the root. By the 11th century, they were already being described as red or yellow and their popularity had spread around the globe.

Daucus carota. (Photo: The Northwest Forager)

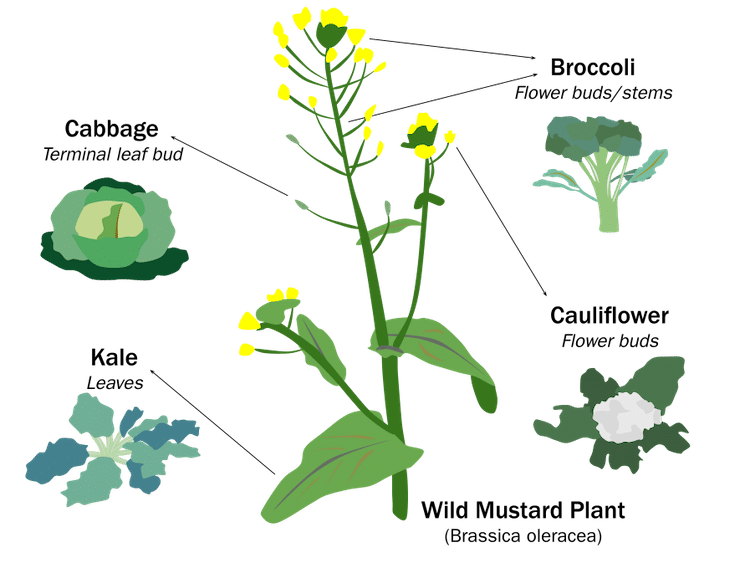

CABBAGE

Brassica oleracea. (Photo: Kulac [CC BY-SA 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons)Did you know that a whole host of green veggies found on your dinner plate can’t actually be found in the wild? Broccoli, brussels sprouts, kale, and cauliflower are just some of the delicious vegetables that can be traced back to one plant—Brassica oleracea. Known as wild cabbage or wild mustard, this cultivator is native to coastal southern and western Europe. It was used as a cultivator because of its nutrient-rich leaves and hardy constitution. By focusing on different parts of the plant, many common vegetables were produced over time.

Photo: Liwnoc [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons